History of Economic Analysis

Introduction

History of Economic Thought (HET) is today a very specialized field in economics pursued by a group of scholars who publish in technical journals and attend specialized conferences. The field is so special that only a few economics departments at major universities offer a HET course in their curriculum. If they do so, it is usually at the undergraduate level.[^fn1] This view of HET is not recent; according to the great late economist Paul Samuelson (1915-2009), "History of thought was a dying industry" already in 1935 when he began his graduate studies in Chicago. Samuelson also thought that the field of economics "burst to life" following "the monopolistic competition revolution, the Keynesian macro revolution, the mathematization revolution, and the econometric inference revolution," implying that what existed before these revolutions was not truly alive. More broadly, if economics is a cumulative scientific process, it implies that the present is "the latest and best final thing". If this view is correct, we should start from today's frontier to understand and study economics and not look back at past theories.

But is this view correct? Should we focus solely on the current frontier of economics, or is there value in exploring the history of economic ideas?

Another giant of economics, Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950), who wrote the seminal "History of Economic Analysis" (1954), offers compelling reasons for studying HET:

Well, why do we study the history of any science? [...] First, [...] Unless that recent treatise itself presents a minimum of historical aspects, no amount of correctness, originality, rigor, or elegance will prevent a sense of lacking direction and meaning from spreading among the students or at least the majority of students.[...] Second, our minds are apt to derive new inspiration from the study of the history of science. [...] Third, the highest claim that can be made for the history of any science or of science in general is that it teaches us much about the ways of the human mind.

- Without historical context, students may lack a sense of direction and meaning in their studies.

- Engaging with the history of economics can inspire new ideas and insights.

- Studying HET teaches us about the workings of the human mind and the evolution of thought.

Consider, for example, the concept of utility maximization, a cornerstone of modern microeconomics. For a new student, this might seem like an abstract and arbitrary assumption. But by tracing its historical origins and development, we can better understand its rationale and limitations.

Moreover, in an era of increasing specialization and technical complexity in economics, the history of thought offers a route to a broader, more holistic understanding. As a graduate student, I recall a gifted colleague presenting a cutting-edge growth model that cleverly incorporated Adam Smith's ideas on specialization - ideas he gleaned from directly engaging with "The Wealth of Nations." This example illustrates how a generalist perspective, cultivated through the study of HET, can enrich and expand the scope of modern technical economics.

Studying HET also allows us to engage with primary sources and form our own interpretations, rather than relying solely on secondary accounts. While the writing style of earlier economists can be challenging for modern readers, directly grappling with original texts is invariably rewarding. I have put some of the original citations in the footnotes to reduce their number and make reading these notes somewhat lighter. I also think that the exercise of rendering some older ideas into modern mathematical language is useful and fun. On the one hand, the simplified mapping of the older writing into mathematical models (here following Samuelson) permits the gain of precision of simpler mechanisms and ideas and may identify logical errors in the arguments. On the other hand, it acknowledges the loss in complexity and depth, a characteristic of any model. In these notes, I aim to provide a curated selection of key original passages, complemented by explanations and mathematical interpretations that translate core ideas into the language of modern economics using mostly Paul Samuelson small models. As we progress chronologically, the need for mathematical elaboration will diminish, as the original works themselves increasingly employ formal methods.

The overarching goal, to borrow Schumpeter's phrase, is to survey the

intellectual efforts that men have made in order to understand economic phenomena or, which comes to the same thing, the history of the analytic or scientific aspects of economic thought.

We will trace the development of two principal strands of intellectual effort in economics: deduction (first using philosophy, then using mathematics) and induction (first using direct empirical observation, then using statistical analysis).

So let us embark on this fascinating journey through the history of economic analysis - exploring the key ideas, debates, and figures that shaped the evolution of economic thought, and in doing so, enriching our understanding of the economic forces that shape our world.

PART I: The Age of Political Economy

The first part of our course is dedicated to the era known as the Age of Political Economy, the precursor to what we now call Economics.

flowchart TD

subgraph ide0 [ETHICS]

A1(Aristotle 350BC) --> A2(Thomas Aquinas 1224-1274)

end

subgraph ide1 [POLITICAL ECONOMY]

subgraph ide11 [Mercantilists]

B1(Thomas Mun 1571-1641)

end

subgraph ide12 [Enlightenment Philosophers]

B2(Hume 1711-1776) --> M1{our first model: <br/> price-specie}

end

subgraph ide13 [Physiocrats]

B3(Richard Cantillon 1680-1734)

B4(Francois Quesnay 1694-1774)

end

subgraph ide21 [Classics]

B2 --> C1

B4 --> C1

C1(Adam Smith 1723-1790)

C2(David Ricardo 1772-1823)

B1 --- C1

C1 --> C2

C1 --> C3(John Stuart Mill 1806-1873)

C1 --> C4(Thomas Malthus 1766-1834)

M2{Second Model: <br/> Classical System}

end

subgraph ide22 [Marxism]

C2 -.-> D1(Karl Marx 1818-1883)

B4 -.-> D1

M3{Third Model: <br/> 2 sectors reproduction}

end

end

subgraph ide2 [ECONOMICS I]

end

ide0 ==> ide1

ide0 ==> ide1

ide1 ==> ide2

ide1 ==> ide2The figure above shows a tree diagram with some of the key thinkers we will encounter in Part I. The diamonds represent small mathematical models developed by Paul Samuelson to formalize specific ideas. While we won't delve into every author in equal depth, and you may not remember every detail, engaging with these original texts and models will provide a rich understanding of the foundations of economic thought. Models are oriented to economists while students with different background can skip them if they wish so.

Before diving into the Age of Political Economy, it's essential to understand the intellectual landscape that preceded it. We will begin by examining the ethical and philosophical foundations laid in ancient Greece, which had a lasting impact on economic thought. These early ideas, particularly those of Aristotle, addressed crucial questions such as fair prices, usury, and the role of economics in society. Aristotle's works, including "Politics" and "Nicomachean Ethics," provided a more explicit and systematic treatment of economic issues than earlier thinkers, setting the stage for centuries of debate and development.

Aristotle's ethical precepts on economic matters, such as the concept of a "fair price" and the prohibition of usury, became the bedrock of medieval economic thought in Europe. His ideas were later adopted and expanded upon by influential scholars like Thomas Aquinas, who integrated them into the framework of Christian theology and ethics.

Following this, we will briefly explore the ideas of a few key 17th-century thinkers who paved the way for the emergence of Political Economy. While these examinations will be brief, they will highlight the crucial intellectual shifts that set the stage for the birth of this new field of inquiry.

Ethics (350 BC - 1500 AD)

The two main economic questions we will focus on in this period are:

- What determines a fair price for a good in an exchange?

- What is the correct level of interest to charge on a loan?

Aristotle (350 BC) defines oikonomikos, the household's management, as having two components. The first component relates to the role of the husband (there was very little space for women in Ancient Greece beyond royalty) in managing the household and acquiring private property, which is composed of instruments (think of capital), and slaves (think of labor). This first component is natural (wealth-getting) ktetike, the art of becoming rich by producing goods and services. Let us read our first extract and marvel at the analytical capabilities of Aristotle.

Seeing then that the state is made up of households, before speaking of the state we must speak of the management of the household. The parts of household management correspond to the persons who compose the household, and a complete household consists of slaves and freemen. Now we should begin by examining everything in its fewest possible elements; and the first and fewest possible parts of a family are master and slave, husband and wife, father and children. We have therefore to consider what each of these three relations is and ought to be: I mean the relation of master and servant, the marriage relation, and thirdly, the procreative relation. And there is another element of a household, the so-called art of getting wealth, which, according to some, is identical with household management, according to others, a principal part of it; the nature of this art will also have to be considered by us. Politics Book I-III

In this passage from his "Politics," Aristotle is setting out his view of the proper management of a household, which he sees as the foundation of the state.

-

Aristotle asserts that the state is composed of households, so to understand the state, we must first understand household management.

-

He identifies the key relationships within a household: master and slave, husband and wife, and father and children. Aristotle believes each of these relationships has a natural hierarchy and proper roles that need to be understood.

-

Aristotle introduces the idea of the "art of getting wealth" or "chrematistike" in Greek. This is the economic aspect of household management.

-

There was debate even then about whether wealth-getting was the same as household management or just a part of it. Aristotle flags this as an issue to be investigated.

-

The mention of "slaves and freemen" and the "master and slave" relationship reflects the fact that slavery was a fundamental part of the ancient Greek household and economy.

Overall, Aristotle is laying out a framework for analyzing the household as an economic and social unit, and flagging key issues he will discuss, such as the proper roles and relationships within a household, and the place of wealth-getting or economic activity in household management. This focus on the household as the foundation of the state and economics is a distinctively Aristotelian perspective that would shape thinking for centuries.

Property is a part of the household, and the art of acquiring property is a part of the art of managing the household; for no man can live well, or indeed live at all, unless he be provided with necessaries. And as in the arts which have a definite sphere the workers must have their own proper instruments for the accomplishment of their work, so it is in the management of a household. Now instruments are of various sorts; some are living, others lifeless; in the rudder, the pilot of a ship has a lifeless, in the look-out man, a living instrument; for in the arts the servant is a kind of instrument. Thus, too, a possession is an instrument for maintaining life. And so, in the arrangement of the family, a slave is a living possession, and property a number of such instruments; and the servant is himself an instrument which takes precedence of all other instruments. Politics Book I-IV

In this passage, Aristotle further elaborates on the economic aspect of household management:

-

Property is a necessary part of the household, and acquiring property is a key aspect of household management, because property is necessary for life.

-

Just as workers need proper tools, a household needs proper instruments, which can be living (like slaves) or non-living (like tools).

-

Aristotle considers slaves to be "living possessions" or "living instruments," reflecting the deeply entrenched institution of slavery in Ancient Greece.

-

Slaves are seen as the most important instruments of a household, taking precedence over inanimate possessions.

This passage provides insight into Aristotle's view of the integral role of property and slaves in the Greek household economy. It's a stark reminder of how deeply the institution of slavery was woven into the social and economic fabric of the ancient world, and how this was justified philosophically.

Aristotle identifies a second method to accumulate wealth. This second method relates to the accumulation of wealth typically achieved through commerce or finance. This is an unnatural (wealth-getting) krematistike, the art of becoming rich from trade and usury, which he writes is the most hated.

There are two sorts of wealth-getting, as I have said; one is a part of household management, the other is retail trade: the former necessary and honourable, while that which consists in exchange is justly censured; for it is unnatural, and a mode by which men gain from one another. The most hated sort, and with the greatest reason, is usury, which makes a gain out of money itself, and not from the natural object of it. For money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest. And this term interest, which means the birth of money from money, is applied to the breeding of money because the offspring resembles the parent. Wherefore of a modes of getting wealth this is the most unnatural. Politics Book I-X

In this passage, Aristotle distinguishes between two types of wealth acquisition:

-

Oikonomia: Household management, which involves acquiring goods to satisfy the needs of the household. This form of wealth-getting is seen as natural and morally acceptable.

-

Chrematistike: The art of retail trade or money-making, which involves the exchange of goods for profit. This form of wealth-getting is seen as unnatural and morally suspect.

Aristotle is particularly critical of usury, the practice of charging interest on loans. He argues that money is meant to be a medium of exchange, not a means of generating more money. The Greek word for interest, "tokos," literally means "birth" or "offspring," and Aristotle uses this metaphor to argue that charging interest is unnatural, as it makes money "breed" money, like a living thing.

This passage reflects several key ideas in Aristotelian economic thought:

- The distinction between the "natural" economy of the household and the "unnatural" world of trade and money-making.

- The ethical suspicion of trade and profit-making as a source of wealth.

- The idea that money is sterile and should not bear interest, an idea that would profoundly influence medieval Christian thought on usury.

Aristotle's views here reflect the economic realities of the largely agrarian, non-commercial society of ancient Greece, and his philosophical commitment to the idea that everything, including economic activities, should follow "natural" purposes.

This is a very negative view of trade and financial activities, which of course existed in Antiquity. Aristotle does not like the idea that in a trade there might be a surplus, namely one of the party that gains more. The part on trade merits further attention for Aristotle's message is that there should be justice in exchange. Drawing on the commutative principle, Aristotle argued for a "just price" - that you should give in value what you receive in value. He also mention a unit, demand, that can be identified as the use value, the ability to satisfy a specific need, that Adam Smith will refer to 2000 years later. He also recognized that money was just a convention, neither good nor bad in itself. Here

For it is not two doctors that associate for exchange, but a doctor and a farmer, or in general people who are different and unequal; but these must be equated. This is why all things that are exchanged must be somehow comparable. It is for this end that money has been introduced, and it becomes in a sense an intermediate, for it measures all things, and therefore the excess and the defect-how many shoes are equal to a house or to a given amount of food. The number of shoes exchanged for a house (or for a given amount of food) must therefore correspond to the ratio of builder to shoemaker. For if this be not so, there will be no exchange and no intercourse.[...] All goods must therefore be measured by someone thing, as we said before. Now this unit is in truth demand, which holds all things together (for if men did not need one another's goods at all, or did not need them equally, there would be either no exchange or not the same exchange); but money has become by convention a sort of representative of demand. The Nichomachean Ethics, Book V-5

These negative ethical views on an exchange, if the exchange is not executed at a fair price, and on interest rates, will have long-lasting consequences. For centuries scholars will try to explain how prices are determined, if these prices are fair, and why it is just to charge an interest rate. In the ideas of economics, there will be not much progress for 1500 years. While Western Europe descended into the Dark Ages in the 5th-6th C., the doctrines of classical philosophy were resurrected by Islamic scholars. Through them, the 13th and 14th century Scholastic theologians recovered classical Greek works and brought their thinking (notably Aristotle) back into the mainstream of European intellectual life. Here, the classic reference is Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274). In his monumental Summa Theologica, he represents the idea that gain by trade is seen as deplorable, maybe even in a stronger sense as it can be, and even a sin. In his words:

We must now consider those sins which relate to voluntary commutations. First, we shall consider cheating, which is committed in buying and selling: secondly, we shall consider usury, which occurs in loans. In connection with the other voluntary commutations no special kind of sin is to be found distinct from rapine and theft. Under the first head there are four points of inquiry: (1) Of unjust sales as regards the price; namely, whether it is lawful to sell a thing for more than its worth? (2) Of unjust sales on the part of the thing sold; (3) Whether the seller is bound to reveal a fault in the thing sold? (4) Whether it is lawful in trading to sell a thing at a higher price than was paid for it? Summa Theologica - By Sins Committed in Buying and Selling Q77, T. Aquinas

We must now consider the sin of usury, which is committed in loans: and under this head there are four points of inquiry: (1) Whether it is a sin to take money as a price for money lent, which is to receive usury? (2) Whether it is lawful to lend money for any other kind of consideration, by way of payment for the loan? (3) Whether a man is bound to restore just gains derived from money taken in usury? (4) Whether it is lawful to borrow money under a condition of usury?[...] I answer that, To take usury for money lent is unjust in this is to sell what does not exist, and this evidently leads to inequality which is contrary to justice. Summa Theologica - By Sins Committed in Loans Q78, T. Aquinas

These views echo Aristotle and had implications for the development of trade. And again, lending for interest was seen as an aberration, having long-lasting implications for the development of finance. There were attempts to overcome this logic by arguing that interests were remunerating time (but time is a common good) or compensation for a default/accident probability, damnum emergens. Slowly Europe was beginning to crawl out of the Dark Ages. Trade was re-emerging, and with it came a new class of people - merchants, with fortunes - who seemed to have no assigned place in the traditional feudal order. And so some Scholastics deployed their new knowledge to try to make sense of this strange new world of markets and money and take different views than Aquinas.

These restrictive attitudes began to change with the Renaissance and the rise of a new philosophical approach based on reason and empiricism. A momentous shift was underway, from the religious and ethical concerns of the medieval world to a new paradigm that would give birth to Political Economy...

flowchart TD

A[Aristotelian Philosophy] --> B[Aquinas & The Scholastics]

subgraph Ethics

E[Restrictions on Trade & Usury]

end

B --> E

E --RUPTURE--- C[Scientific Revolution]

C ==> H[POLITICAL ECONOMY]Interlude: From Ethics to Reason, or from Oikonomikos to Political Economy

Let me take a small detour from the HET and present a small series of extracts from Renaissance thinkers. A sharp turning away from the medieval tradition that put God and the afterlife at the center of everything occurred during the 15th century. This new vision is revealed with flamboyant confidence by Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) a Florentine thinker who wrote

We (God) have made you a creature neither of heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, in order that you may, as the free and proud shaper of your own being, fashion yourself in the form you may prefer. It will be in your power to descend to the lower, brutish forms of life; you will be able, through your own decision, to rise again to the superior orders whose life is divine. (the man answers) Oh unsurpassed generosity of God the Father, oh wondrous and unsurpassable felicity of man, to whom it is granted to have what he chooses, to be what he wills to be! On the Dignity of Man (1480)

According to this view, man is not merely the measure of all things as the Greek Sophist Protagoras had proclaimed in the fifth century. He is, in fact says Pico, more than mortal. He is unlimited by nature. He is entirely free to shape himself and to acquire whatever he wants. Please observe too that it is not his reason that will determine human actions but his will alone, free of the moderating control of reason.

Another Florentine, Niccolo Machiavelli moved further in the same direction for him:

...because fortune is a woman, and if you wish to keep her under it is necessary to beat and ill-use her; and it is seen that she allows herself to be mastered by the adventurous rather than by those who go to work more coldly. The Prince (1532)

Machiavelli is basically saying that we can control our own fate.

Francis Bacon, although influenced by Machiavelli, tilts the balance towards reason. He urges human beings to employ their reason to force nature to give up its secrets. To master nature in order to improve man's material life. He assumes that such a course will lead to progress and the general improvement of the human condition. That sort of thinking lay at the heart of the scientific revolution and remains the faith upon which modern science and technology rests. A couple of other English political philosophers, Hobbs and Locke, applied a similar novelty and modernity to the sphere of politics. They based their understanding on the common passions of man for comfortable self-preservation and discovering something they called natural rights that belonged to a man either as part of nature or as the gift of a benevolent and a reasonable god. Man was seen as a solitary creature, not inherently a part of society. In that environment of emancipation where the speculative method applies and rational deductive procedure is applied to an object of study, some wanted to emancipate economics from the individual sphere and project it also to public activity.

Before Political Economy

In the 17th and 18th centuries, a diverse group of thinkers - philosophers, public servants, merchants, and even physicians - sought to understand the economy in a more systematic and analytical way. Moving beyond the narrow ethical concerns of earlier periods, they asked new questions about the sources of national wealth, the effects of government intervention, the role of money and trade, and the flows of goods and money between sectors. This marked the birth of Political Economy as a distinct field of inquiry. One of the first question regarded foreign trade.

Mercantilism

In the 17th century, one puzzling question was the performance of the Dutch. Holland was a small country that had only come into existence in the 1580s after a revolt against its Spanish Hapsburg rulers. But it had managed to spectacularly transform itself into one of the wealthiest countries in the world, with outposts that stretched across the globe, from Nagasaki to New Amsterdam, from the Artic Circle to South Africa, and whose citizens enjoyed probably the highest standard of living of that time. Holland had a small population, very little land, and virtually no natural resources. However, Holland maintained a favorable balance of trade with foreign countries: they exported expensive 'high-value' manufactured goods (notably finished cloth and iron goods like tools, guns, etc.) and only imported cheap 'low-value' primary commodities (raw wool and iron ore, inputs needed for their industries). That meant foreign money (gold & silver) constantly flowed into Holland. The 'Mercantilist' policy formula was quickly devised: Export as much as possible and import as little as possible. Make sure your exports are high-value goods – luxuries, manufactures – which will bring in a lot of money. If you must import, import only essential low-value goods that are absolutely necessary for your industries – that is, only raw materials and other basic necessities you simply cannot find at home.

The Mercantilists expected - or demanded - that the government take an active role in this, and make "protectionism" a central part of government policy. The government was at various times by different authors called upon to forbid or restrict anybody from taking money out of the country by all sorts of controls and laws, impose tariffs and quotas to discourage imports and hand out export subsidies ('bounties') to domestic exporters. In an extreme version of mercantilism, Bullionism, Gold is identified as the primary form of wealth and the primary policy prescription is to run an external surplus. You could run deficits with countries that were providing raw materials if it permitted to run surpluses with others. An important mercantilist was Thomas Mun (1571-1641) who was for a time the director of the East India Company.

Although a Kingdom may be enriched by gifts received, or by purchase taken from some other Nations, yet these things are uncertain and of small consideration when they happen. The ordinary means therefore to encrease our wealth and treasure is by Forraign Trade, wherein we must ever observe this rule: to sell more to strangers yearly than we consume of theirs in value. For suppose that when this Kingdom is plentifully served with the Cloth, Lead, Tinn, Iron, Fish and other native commodities, we doe yearly export the overplus to forraign Countries to the value of twenty two hundred thousand pounds; by which means we are enabled beyond the Seas to buy and bring in forraign wares for our use and Consumptions, to the value of twenty hundred thousand pounds; By this order duly kept in our trading, we may rest assured that the Kingdom shall be enriched yearly two hundred thousand pounds, which must be brought to us in so much Treasure; because that part of our stock which is not returned to us in wares must necessarily be brought home in treasure. England Treasure by Forraign Trade - Chapter II, The means to enrich this Kingdom, and to encrease our Treasure, T. Mun

This view favors the merchants, hence the name mercantilism, which basically prescribes protectionism, and led to the creation of great national companies such as the British East India Company in 1600. They also recommended that the government actively help domestic private businessmen set up high-value import-substitution and export-oriented industries. The crown was urged to subsidize these industries, whether directly or indirectly. Infrastructure investment, like roads and ports, to facilitate the export trade, was to be encouraged. In order to minimize "destructive competition" at home, many Mercantilists believed that charter companies had a better chance of succeeding abroad if they were granted a charter with exclusive government-guaranteed monopolies over particular areas of industry and trade. The Mercantilist emphasis on trade surpluses and government intervention would soon face challenges from a new generation of thinkers who saw free trade and market forces as the keys to national prosperity.

Prices and the quantity theory

Quickly reverse thinking occurred: towards the end of the 17th century, the idea that state intervention was harmful to economic development started to spread. Economic thinking also started to be more analytical, for example, the effort to understand how prices were determined returned in vogue leaning towards the explanation that prices were determined by production more than demand factors. - Intrinsic value, or fundamental value is the price as the value of production although market price can differ depending on demand factors. Here is what Richard Cantillon (1680-1734) has to say about the determination of prices:

If two Acres of Land are of equal goodness, one will feed as many Sheep and produce as much Wool as the other, supposing the Labour to be the same, and the Wool produced by one Acre will sell at the same price as that produced by the other. If the Wool of the one acre is made into a suit of coarse Cloth and the Wool of the other into a suit of fine Cloth, as the latter will require more work and dearer workmanship it will be sometimes ten times dearer, though both contain the same quantity and quality of Wool. [...] The price of a pitcher of Seine Water is nothing, because there is an immense supply which does not dry up; but in the Streets of Paris people give a sou for it—the price or measure of the Labour of the Water carrier. By these examples and inductions it will, I think, be understood that the Price or intrinsic value of a thing is the measure of the quantity of Land and Labour entering into its production, having regard to the fertility or produce of the Land and to the quality of the Labour. But it often happens that many things which have actually this intrinsic value are not sold on the Market according to that value: that will depend on the Humours and Fancies of men and on their consumption.

Essay on the Nature of Commerce Part I, Chapter X

We are far from the ethical preoccupations of earlier times. Still, the analytical effort to understand how prices are determined is remarkable. prices are determined by the quantity of land and labor which are seen as the two production factors. However, the degree to which people want or like a good might also matter. The intellectual effort is also turned to "macro" phenomena like the level of activity, and here the deduction of the effects of the quantity of Money, at that time backed by gold, on the level of activity are deemed to be important. Again Cantillon:

If mines of gold or silver be found in a State and considerable quantities of minerals drawn from them, the Proprietor of these Mines, the Undertakers, and all those who work there, will not fail to increase their expenses in proportion to the wealth and profit they make: they will have over and above what they need to spend. All this money, whether lent or spent, will enter into circulation and will not fail to raise the price of products and merchandise in all the channels of circulation which it enters. Increased money will bring about increased expenditure and this will cause an increase in Market prices in the highest years of exchange and gradually in the lowest.[...] Mr. Locke lay it down as a fundamental maxim that the quantity of produce and merchandise in proportion to the quantity of money serves as the regulator of Market price [...] If the increase in actual money comes from Mines or gold or silver in the State the Owner of these Mines, the Adventurers, the Smelters, Refiners, and all other workers will increase their expenses in proportion to their gains. They will consume in their households more Meat, Wine, or Beer than before, will accustom themselves to wear better cloaths, finer linen, to have better furnished Houses and other choicer commodities. They will consequently give employment to several Mechanicks who had not so much to do before and who for the same reason will increase their expenses: all this increase in Meat, Wine, Wool, etc.[...] diminishes of necessity the share of the other inhabitants of the State who do not participate at first in the wealth of the Mines in question. The altercations of the market, or the demand for Meat, Wine, Wool, etc., being more intense than usual, will not fail to raise their prices. These high prices will determine the Farmers to employ more land to produce them in another year: these same Farmers will profit by this rise of prices and will increase the expenditure of their Families like the others.

Essay on the Nature of Commerce Part II, Chapter VI, R. Cantillon

This line of reasoning can be cast in our first equation, the famous $$ M\gamma = PQ $$

where M is money, \(\gamma\) velocity, P price level, and Q output (the level of activity). The first algebraic rendering of this equation is probably due to irving Fisher in 1911. Reading the passage above, we understand that Cantillon debates on what adjusts and when. He says that an increase in Money Supply will ultimately result in an increase in Prices, but will also increase activity in the short run. We will use this equation in our first model just below.

Free Trade: The Price-Specie adjustment mechanism

The Price-Specie Flow Mechanism, a self-correcting process for trade imbalances, is one of the most influential economic ideas put forward by the Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776). This elegant theory, which demonstrated how market forces could automatically balance trade between nations without the need for government intervention, stood in stark contrast to the Mercantilist policies of the time. The Price-Specie Flow Mechanism's significance and lasting impact on economic thought make it worthy of special attention. To better understand its workings, we will explore a "modern" economic model of the mechanism, drawing on the exposition by renowned economist Paul Samuelson. Before delving into the model, let us first consider Hume's original description of the concept:

IT is very usual, in nations ignorant of the nature of commerce, to prohibit the exportation of commodities, and to preserve among themselves whatever they think valuable and useful[...]It is well known to the teamed, that the ancient laws of ATHENS rendered the exportation of figs criminal; that being supposed a species of fruit so excellent in ATTICA, that the ATHENIANS deemed it too delicious for the palate of any foreigner[...] The same jealous fear, with regard to money, has also prevailed among several nations; and it required both reason and experience to convince any people, that these prohibitions serve to no other purpose than to raise the exchange against them, and produce a still greater exportation.... But there still prevails, even in nations well acquainted with commerce, a strong jealousy with regard to the balance of trade, and a fear, that all their gold and silver may be leaving them...Suppose four-fifths of all the money in BRITAIN to be annihilated in one night, and the nation reduced to the same condition, with regard to specie, as in the reigns of the HARRYS and EDWARDS, what would be the consequence? Must not the price of all labour and commodities sink in proportion, and every thing be sold as cheap as they were in those ages? What nation could then dispute with us in any foreign market, or pretend to navigate or to sell manufactures at the same price, which to us would afford sufficient profit? In how little time, therefore, must this bring back the money which we had lost, and raise us to the level of all the neighbouring nations? Where, after we have arrived, we immediately lose the advantage of the cheapness of labour and commodities; and the farther flowing in of money is stopped by our fulness and repletion.

Political Essays - Of the balance of trade, Hume

In Hume's description, we can readily identify the key components of the re-equilibrating mechanism. When a country experiences a trade surplus, it receives an inflow of gold as payment for its exports. This influx of gold increases the money supply within the country, which, in turn, leads to a rise in prices. Conversely, a country with a trade deficit sees an outflow of gold, reducing its money supply and causing prices to fall.

The resulting changes in prices have an impact on the competitiveness of each country's goods in international markets. As prices rise in the surplus country, its exports become more expensive and less attractive to foreign buyers. Simultaneously, the deficit country's falling prices make its goods more competitive and appealing to international consumers. This shift in relative prices encourages exports from the deficit country and discourages imports, while the opposite occurs in the surplus country.

Over time, these adjustments in competitiveness serve to rebalance trade between the two countries. The surplus country's exports decrease, and its imports increase, while the deficit country experiences a growth in exports and a reduction in imports. This automatic rebalancing process, driven by market forces, ultimately brings the trade relationship back into equilibrium.

The implications of Hume's Price-Specie Flow Mechanism are significant, as they provide a strong argument for the benefits of free trade. By allowing market forces to operate without interference, countries can naturally correct trade imbalances and maintain a healthy, mutually beneficial exchange of goods and services. This stands in sharp contrast to the Mercantilist policies of the previous century, which advocated for government intervention, protectionism, and the hoarding of precious metals.

To further clarify the workings of the Price-Specie Flow Mechanism, let us now turn to a simple mathematical exposition designed by Paul Samuelson. This modern economic model will help us better understand the dynamics at play and the key variables involved in the re-equilibrating process.

The price-specie model statement

-

Let \(P\) stand for gold price(s) at home, \(P^{*}\) for price(s) abroad

-

\(M^{*}\) stands for foreign (gold) money supply

-

\(M\) for domestic gold supply

-

\(Q\) and \(Q^{*}\) for the total outputs at home and abroad

-

Ignoring capital movements, let \(B\) be the gold value of the balance of trade – the surplus of exports over imports if positive, or deficit if negative.

represents the idea that the trade balance improves if the domestic economy is more competitive, namely, goods cost less than abroad.

is the famous quantity theory of Money. The central question (see Hume and Cantillon quotes above) is when \(M\) changes, what adjusts (and when)? \(P\) or \(Q\) or \(\gamma\)? For Hume, in this citation but not in other parts of his writings, it is \(P\). $$ B =\dot{M}=-\dot{M}^{*} $$

represents the outflow of money (gold) to pay the deficit, or the inflow that corresponds to a surplus. $$ M+M^{*} =\bar{M} $$ represents the equilibrium in the total amount of Gold in the system (World).

So let us collect all the equations of our model: $$ \begin{aligned} B &=f\left(\frac{P}{P^{}}\right)\ \ PQ &=\gamma M \ P^{}Q^{} &=\gamma M^{} \ B &=\dot{M}=-\dot{M}^{} \ M+M^{} &=\bar{M}\end{aligned} $$ We have an aggregate equation per region that links prices, output, and money. An equation that represents the trade balance, an equation that relates the trade balance to payments (the current account) and the aggregate (two regions sum) supply of Money. The reasoning of Hume according to the system can be spelled out as follows: if \(M\) decreases suddenly (he wants to describe the outflow of gold), then \(P\) will fall, and if \(Q\) is maintained, \(B\) will become positive as the relative price decrease makes the country more competitive reversing the initial outflow of money. So, let's solve the system and get an equation for the flow of money (in equilibrium): $$ \dot{M}=f\left(\frac{MQ^{*}}{\left(\bar{M}-M\right)Q}\right) $$

The price-specie model steady state

In Stationary - Steady State (think of the Long Run when the adjustment is terminated): $$ B=f(1)=0 $$ $$ f\left(\frac{MQ^{}}{\left(\bar{M}-M\right)Q}\right)=0 $$ Therefore the solution for \(M\) in the long-run is: $$ M^{LR}=\frac{Q}{Q^{}+Q}\bar{M}, $$ which shows that in the Long Run, the quantity adjusts towards a constant proportion given by the production level (taken as given). Consider now the dynamic adjustment assuming an initial condition \(M_0\) different from the long run value. If \(M_0<M^{LR}\), namely, the stock of gold is below the long-run value, the relative price ratio is \(\frac{MQ^{*}}{\left(\bar{M}-M\right)Q}<1\) which favors exports and imply an external surplus with an accumulation of gold: \(\dot{M}>0\). The shape of the adjustment depends on the properties of \(f\) but it occurs until the relative price reaches unity. If \(M_0>M^{LR}\) the adjustment occurs through trade deficits. You can try to plot what just described using some specific functional form, for example: $$ f(P/P^) = (P/P^)^{(\alpha-1)}- 1, $$

where \(\alpha< 1\). Here is a simulation from two different starting points, one corresponding to a surplus and one to a deficit.

We just described a long-run adjustment without friction, and the mathematical model gives a neat representation and permits an intellectual check of the reasoning.

As Schumpeter used to put it, we can applaud Hume’s performance in specifying a self-correcting mechanism that impressed people for two hundred years." P.A. Samuelson

One caveat is the focus on the long-run, as in reality the short run might be more complex. In fact, Hume was very aware that the short run was important:

Accordingly we find, that, in every kingdom, into which money begins to flow in greater abundance than formerly, every thing takes a new face; labour and industry gain life; the merchant becomes more enterprising, the manufacturer more diligent and skilful, and even the farmer follows his plough with greater acrity and attention. This is not easily to be accounted for, if we consider only the influence which a greater abundance of coin has in the kingdom itself, by heightening the price of commodities, and obliging every one to pay a greater number of these little yellow or white pieces for every thing he purchases. And as to foreign trade, it appears, that great plenty of money is rather disadvantageous, by raising the price of every kind of labour. To account, then, for this phenomenon, we must consider, that, though the high price of commodities be a necessary consequence of the encrease of gold and silver, yet it follows not immediately upon that encrease; but some time is required before the money circulates through the whole state, and makes its effect be felt on all ranks of people. At first, no alteration is perceived; by degrees the price rises, first of one commodity, then of another; till the whole at last reaches a just proportion with the new quantity of specie which is in the kingdom. In my opinion, it is only in this interval or intermediate situation, between the acquisition of money and rise of prices, that the encreasing quantity of gold and silver is favourable to industry.

Hume Political Essays - Of Money, D. Hume

In the chapter on Money, Hume acknowledges a short-run effect on economic activity that he did not consider in the price-specie adjustment mechanism. Samuelson extends the model to incorporate this additional insight, but for the sake of brevity, we will not delve into the details here. Instead, let us pause for a moment to reflect on the process we just undertook. To be precise, it was Samuelson who mapped Hume's theory, originally expressed in words, into mathematical form. This exercise has taught us that we can indeed scrutinize the reasoning behind a theory, but doing so requires explicitly spelling out a set of assumptions.

However, this is where a potential pitfall lies: if we fail to constantly keep in mind the limited scope of reality that our assumptions imply, we risk misusing the model. For instance, we might overlook the fact that the activity level can be influenced by current imbalances through channels other than competitiveness, or that the described adjustment process implies that prices differ across countries during the transition period. It is crucial to ask ourselves whether these implications are reasonable. If they are not, then we are left with a result that hinges on a flawed hypothesis.

The economy as a circular system - input/output

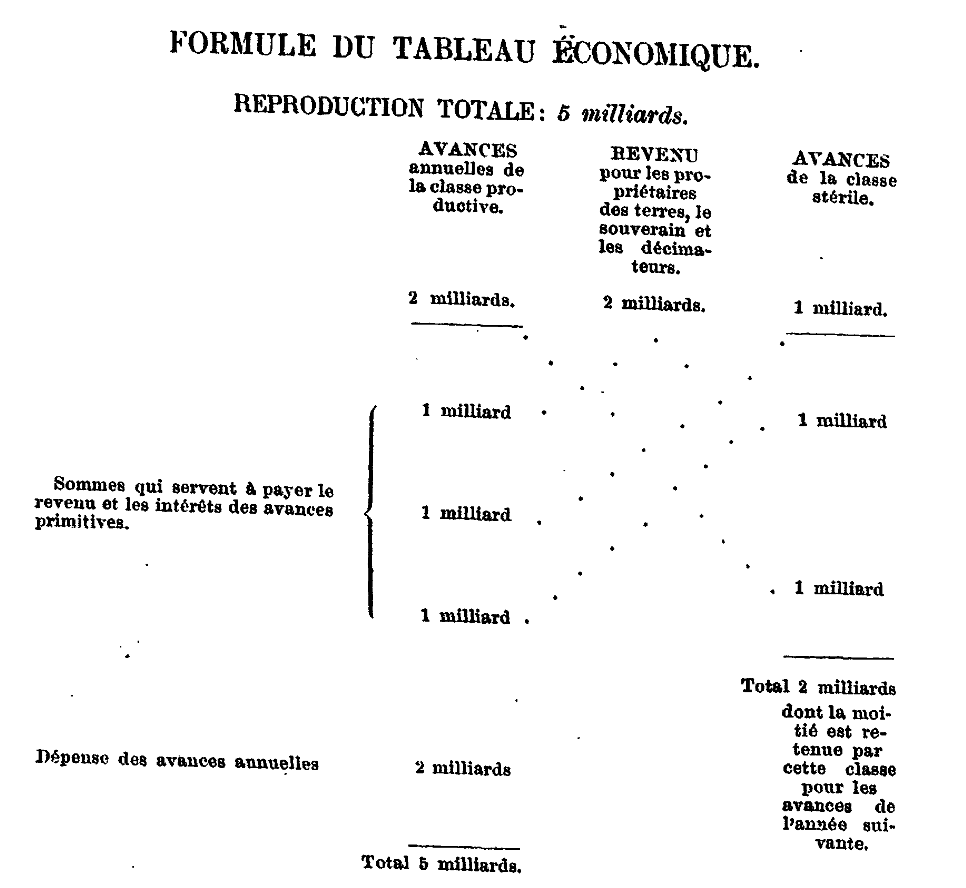

The last pre-Classic movement we will mention, the Physiocratic school, might be the first "true" school, with Francois Quesnay (1694-1774) as the central figure. Quesnay and his disciples had very innovative ideas, for example, they introduced the notions of productive and unproductive labour, by means of which the real source of wealth was found in the net product obtained by applying labour to land. You can think of a production function where the special factor of production is land and a second factor of production, productive labour, complements the land and results in value-added, produit net. Another type of labour, the one not applied to land would be unproductive in their view: sterile. Why would manufacturing and commerce be sterile sectors? Their arguments were grounded in metaphysics. They differentiated between the ordre naturel (natural order, or the social order dictated by nature's laws) and the ordre positif (positive order, or the social order dictated by human ideals). The idea of interdependence among the various productive sectors and the related idea of macroeconomic equilibrium was extremely innovative by representing the economic exchanges as a circular flow of money and goods among the various economic sectors. Also the displacement of scientific interest from the stock of wealth to the flow of net product is of great importance. Finally, they championed the idea of laissez-faire, namely minimizing the state intervention and the impot unique, one single tax to finance a minimal government. Their representation of the flows between sectors was rendered in the famous Tableau Economique , a primordial Input-Output System:

graph LR;

A[Productive Class] -- 1 milliard --> B[Non-Productive Class]

A -- 2 milliards --> A

B -- 2 milliards --> A

A -- 2 millard --> C[Distributive Class]

C -- 1 milliard --> A

C -- 1 milliard --> B-

The productive class pays two milliard in rent to the distributive class and one milliard to the sterile class to buy manufactured articles and spends two milliard within the agricultural sector to buy raw materials, wage goods, and means of production.

-

The distributive class will spend its income in the following way: one milliard to the sterile class and the other one milliard to the productive class to buy, respectively, manufactured goods and agricultural products.

-

The sterile class, which has received two milliard, half from the distributive class and half from the farmers, will spend it all on the productive class to buy its inputs and necessary consumer goods.

-

The three milliard that the productive class has spent outside the agricultural sector will come back to it; so that the cycle can begin again. He viewed this system as a natural order and therefore laissez-faire would be best. A second implication was to simplify tax system and create a unique tax on the produit net. And here a picture of the original one published in 1758:

Political Economy

The industrial revolution that started in the United Kingdom in the second part of the 18th century strongly impacted economic thinking. In 1776, Adam Smith (1723-1790), a former professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, published the Wealth of Nations (WoN). The WoN is usually identified as the first "textbook" in Political Economy, composed of 5 books on the workings of a Society of Perfect Liberty. It represents a synthesis that organized economic thought for the following 40 years. While it is usually identified with the "invisible hand," its contents are better described as an overarching effort to conceptualize the forces and the social organization that result in the phenomena of economic growth. Smith's treatise went against the British laws that restricted internal and external commerce, many of which had been introduced during the Mercantilist era, and proposed a new reformed system of 'natural liberty.' The latter required the careful exposition of the economic principles underlying the system.

Adam Smith

While "The Wealth of Nations" is sometimes criticized for being a messy and inconsistent book, I believe that this view is misguided. Although there are indeed some inconsistencies, such as in Smith's explanation of what determines prices, the overall logic of his overarching argument about how nations prosper is remarkably coherent and insightful[^fnwon1].

At its core, Smith's theory posits that the division of labor and the consequent increase in productivity are the central factors driving the wealth of nations. By breaking down production processes into specialized tasks, workers can become more skilled and efficient, leading to higher output and economic growth. However, Smith recognizes that for this increased production to be sustainable, there must be a sufficiently large market to absorb the goods and services produced.

This brings us to the importance of scale in Smith's analysis. The size of the market, which is influenced by factors such as geography and transportation, plays a crucial role in determining the extent to which the division of labor can be implemented. A larger market allows for greater specialization and economies of scale, leading to higher productivity and economic growth.

In addition to market size, Smith identifies demography as another critical factor in the growth of living standards. A larger population provides a greater pool of labor, which can be employed in increasingly specialized roles. This, in turn, allows for a more extensive division of labor and the associated benefits of increased productivity.

A key implication of the division of labor is the necessity of trade. As workers become more specialized, they rely on the exchange of goods and services to meet their diverse needs. This realization leads Smith to attempt to postulate a theory of value or price determination, which is essential for understanding how trade operates and how prices are set in the market.

To better understand Smith's arguments, let us focus on a schematic view of Book 1 of "The Wealth of Nations," which lays out the foundational principles of his economic theory.

graph TD

A[Labor as the central productive input] --> B(division of labor increases its productivity)

C(The division of labour is a consequence of truck, barter and exchange market) --> B

D[The extent of the division of labour depends on the size of the market]-->B

B --> E[The specialization brought by the division of labor caused the appearence of money to facilitate exchange]

E --> F(Nominal prices and real Prices)

F --> G(The real price is the content of labor of the commodities)

G --> H(Natural and market price of commodities)

H --> L(Wages)

H --> K(Profits)

H --> M(Rents)

Let us read a few passages on labor specialization.

To take an example, therefore, from a very trifling manufacture; but one in which the division of labour has been very often taken notice of, the trade of the pin-maker; a workman not educated to this business[...] could scarce, perhaps, with his utmost industry, make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make twenty. [...]But in the way in which this business is now carried on, not only the whole work is a peculiar trade, but it is divided into a number of branches, of which the greater part are likewise peculiar trades. One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations[...]Those ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day.

This great increase of the quantity of work which, in consequence of the division of labour, the same number of people are capable of performing, is owing to three different circumstances; first, to the increase of dexterity in every particular workman; secondly, to the saving of the time which is commonly lost in passing from one species of work to another; and lastly, to the invention of a great number of machines which facilitate and abridge labour, and enable one man to do the work of many.

Wealth of Nations - Of the Division of Labour chapter I, A. Smith

Smith identifies in the division of labor three consequences that increase productivity. First, each worker becomes more skilled in the specific task. Second the process of production is accelerated. Finally, it incentivizes the invention of machines/instruments to perform a specific task. Growth and the living standard increase occur through productivity growth[^nfwon2]. But why would we specialize to produce more? Here, the explanation is central to the system of liberty: human nature that follows its own interest. This view reflects Smith's beliefs on man as an individual whose morality springs from the hedonic calculus.

This division of labour, from which so many advantages are derived, is not originally the effect of any human wisdom, which foresees and intends that general opulence to which it gives occasion. It is the necessary, though very slow and gradual consequence of a certain propensity in human nature which has in view no such extensive utility; the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

Wealth of Nations - Of the Principle which gives occasion to the Division of Labour - chapter II

Finally for this process of specialization to happen you need a market of a certain scale[^fnwon3].

Regarding the determination of prices, or the value of goods exchanged, I find little innovation in Smith's work compared to Cantillon's earlier contributions. Smith distinguishes between value in use, which is linked to what we would call the demand price, and value in exchange[^fn3]. He presents four different theories of value: the labor-commanded[^fn4] theory, the labor-embodied theory, the adding-up (cost of production [^fn5]) theory, and a disutility of work theory. While this variety of theories might confuse the reader, Smith ultimately favours the cost of production theory and dedicates the remainder of Book I to providing theories for determining the components of natural price.

However, if value represents the price of production inputs, the question arises: how are these inputs determined? Specifically, what determines the wage, the rate of profit, and the rent? What factors influence the natural price levels? Smith proposes the following mechanisms to determine the "natural" price of each of the three inputs. For wages, he observes that employers have greater bargaining power than workers and that unions are essentially prohibited. Furthermore, workers are paid weekly and, therefore, cannot resist living without wages for an extended period. Consequently, in the long run, wages tend towards the subsistence level, which allows for reproduction but not much more—a theory that Malthus will later refine. Smith concedes that economic progress can improve wages over time and acknowledges that labor is not homogeneous, implying that wages are not uniform across all occupations. Factors such as the difficulty of a job, the skills required by a profession, or even chance can lead to wage disparities. In modern terms, he nearly specifies a Mincerian equation. The other two natural prices—profit and rent—are not explained in great detail, although the profit rate is understood as a reward for risk, and rent is seen as a residual value after paying wages and interest. Finally, Smith argues that competition (the system of perfect liberty, which cannot be taken for granted, as he writes[^fn6]) causes market prices to tend toward their natural level, although they can fluctuate below and above the natural level implied by the natural level of input prices. Smith's exposition will remain a central part of the classical theory of distribution until the marginalist revolution.

There is in every society or neighbourhood an ordinary or average rate both of wages and profit in every different employment of labour and stock...There is likewise in every society or neighbourhood an ordinary or average rate of rent... These ordinary or average rates may be called the natural rates of wages, profit, and rent, at the time and place in which they commonly prevail. When the price of any commodity is neither more nor less than what is sufficient to pay the rent of the land, the wages of the labour, and the profits of the stock employed in raising, preparing, and bringing it to market, according to their natural rates, the commodity is then sold for what may be called its natural price[...]. The actual price at which any commodity is commonly sold is called its market price. It may either be above, or below, or exactly the same with its natural price. The market price of every particular commodity is regulated by the proportion between the quantity which is actually brought to market, and the demand of those who are willing to pay the natural price of the commodity, or the whole value of the rent, labour, and profit, which must be paid in order to bring it thither. Such people may be called the effectual demanders, and their demand the effectual demand; since it may be sufficient to effectuate the bringing of the commodity to market. It is different from the absolute demand. A very poor man may be said in some sense to have a demand for a coach and six; he might like to have it; but his demand is not an effectual demand, as the commodity can never be brought to market in order to satisfy it.

When the quantity of any commodity which is brought to market falls short of the effectual demand, all those who are willing to pay the whole value of the rent, wages, and profit, which must be paid in order to bring it thither, cannot be supplied with the quantity which they want. Rather than want it altogether, some of them will be willing to give more. A competition will immediately begin among them, and the market price will rise more or less above the natural price, according as either the greatness of the deficiency, or the wealth and wanton luxury of the competitors, happen to animate more or less the eagerness of the competition. [...]When the quantity brought to market exceeds the effectual demand, it cannot be all sold to those who are willing to pay the whole value of the rent, wages, and profit, which must be paid in order to bring it thither. Some part must be sold to those who are willing to pay less, and the low price which they give for it must reduce the price of the whole. The market price will sink more or less below the natural price, according as the greatness of the excess increases more or less the competition of the sellers, or according as it happens to be more or less important to them to get immediately rid of the commodity. [...]When the quantity brought to market is just sufficient to supply the effectual demand, and no more, the market price naturally comes to be either exactly, or as nearly as can be judged of, the same with the natural price.

All the different parts of its price will soon sink to their natural rate, and the whole price to its natural price. The natural price, therefore, is, as it were, the central price, to which the prices of all commodities are continually gravitating. Different accidents may sometimes keep them suspended a good deal above it, and sometimes force them down even somewhat below it. But whatever may be the obstacles which hinder them from settling in this centre of repose and continuance, they are constantly tending towards it...A monopoly granted either to an individual or to a trading company has the same effect as a secret in trade or manufactures. The monopolists, by keeping the market constantly understocked, by never fully supplying the effectual demand, sell their commodities much above the natural price, and raise their emoluments, whether they consist in wages or profit, greatly above their natural rate...

Smith also writes in Book II on capital accumulation, which goes hand in hand with the division of labor. In this part, he remarks that Money is not to be confounded with revenue or, in more modern terms, output, but he considers it as part of the capital stock. Most notably, he recognizes the important role of Banks in financing the economy, allowing production to increase and, therefore, the reason for banks to receive a "legal" interest rate[^fn7]. Finally in Book IV, Smith presents the list of tasks that the sovereign should have: police, army, justice, and remarkably public work, where he seems to foresee the theory of public goods.

...First, the duty of protecting the society from violence and invasion of other independent societies; secondly, the duty of protecting, as far as possible, every member of the society from the injustice or oppression of every other member of it, or the duty of establishing an exact administration of justice; and, thirdly, the duty of erecting and maintaining certain public works and certain public institutions which it can never be for the interest of any individual, or small number of individuals, to erect and maintain; because the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals,though it may frequently do much more than repay it to a great society. Wealth of Nations - Book 4 - Chapter IX

We cannot not mention the quote of the invisible hand:

As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

Wealth of Nations - Of Restraints upon the Importation from Foreign Countries of such Goods as can be produced at Home Book IV - Chapter II

The popular interpretation is that what is best for the individual is also best for society. In modern rendering the connection between competition and social efficiency. An important aspect is that this quote comes from the Book where Smith attacks the Mercantilist system and encourages free trade.

Thomas Malthus

Thomas Malthus (1766-1834), the author of the influential "Essay on the Principle of Population" (1798), made two significant contributions to economic thought that deserve brief mention. First, Malthus developed a theory of population growth that would later become the central hypothesis for the "iron law of wages," refining Smith's concept of the natural wage rate determination. According to Malthus, the natural (unchecked) rate of population growth invariably exceeds the growth of means of subsistence. This disparity implies that actual (checked) population growth is kept in line with food supply growth through two mechanisms: "positive checks," such as starvation and disease, which elevate the death rate; and "preventive checks," like the postponement of marriage, which keep the birth rate down.

Malthus's hypothesis suggests that the actual population always tends to push above the available food supply. As a result, any efforts to improve the conditions of the lower classes by increasing their incomes or enhancing agricultural productivity would ultimately prove futile, as the induced population growth would completely absorb the additional means of subsistence. Malthus argued that as long as this tendency persists, society's improvement and "perfectibility" will remain out of reach. He pessimistically concluded that the future of mankind would always be marred by "misery and vice" due to this fundamental imbalance between population growth and the means of subsistence[^fn8]"

David Ricardo

David Ricardo (1772-1823) and his "Principles of Political Economy and Taxation" (1817) deserves a more in-depth examination due to the highly articulated and rigorous nature of his formulation of classical theories. Although Ricardo does not employ algebra, his exposition achieves a level of analytical clarity that brings his book closer to a modern textbook. The stated objective of Ricardo's work is to determine the law of distribution between different classes: workers, who spend their wage income on necessities; capitalists, who save most of their profit income and reinvest it; and rentiers[^fn11], who spend their rental income on luxuries.

To achieve this goal, Ricardo needed a precise theory of prices (value), as opposed to the three or four theories presented by Smith. For Ricardo, the most appropriate theory was the "labor-embodied" theory of value, which argues that the relative "natural" prices of commodities are determined by the relative hours of labor expended in their production. However, Ricardo recognized a problem that arose when considering capital: as different industries apply varying amounts of capital per laborer, the rate of profit would also differ across industries. If Ricardo then assumed that the rates of profit across different industries were equalized (as free competition would imply), the relative prices would vary with wages.

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation - On Value - Chapter I

The value of a commodity, or the quantity of any other commodity for which it will exchange, depends on the relative quantity of labour which is necessary for its production, and not on the greater or less compensation which is paid for that labour.

Not only the labour applied immediately to commodities affect their value, but the labour also which is bestowed on the implements, tools, and buildings, with which such labour is assisted.

The principle that the quantity of labour bestowed on the production of commodities regulates their relative value considerably modified by the employment of machinery and other fixed and durable capital.

Ricardo understood that the labor theory of value would only work if the degree of capital intensity were the same across all sectors. He proposed two ways to address this dilemma. First, he made the empirical argument that firms apply capital roughly proportional to the amount of labor invested. In this case, when profits are equalized, the resulting prices would not differ significantly from the values implied by the labor embodied. Using numerical examples, Ricardo demonstrated that the deviation of relative prices from the value of labor content due to capital was small, on the order of 6%-7%, and thus concluded that using the simple form of the labor value theory was an acceptable approximation. This approach is what Stigler (1958) has called Ricardo's "93% labor theory of value."

The second solution was to find a commodity that has the average capital per worker, so that its price would reflect the labor-embodied value and not vary with changes in distribution. Ricardo called this the "invariable standard of value" but acknowledged that it was impossible to find one[^fn12]. As a result, he settled on gold as the closest approximation. The logical construction of Ricardo's arguments is noteworthy: he delves into as many logical details as possible and makes simplifying hypotheses to reach precise conclusions. For example, he assumes that capital's contribution to value can be measured in labor units and approximated to 6%-7%, and that gold can measure absolute value as its labor content is taken to be invariable.

Although not entirely robust, Ricardo uses his price theory to determine class distribution, making one of his most important contributions in the process: the theory of rents, which introduces the concept of decreasing returns to land cultivation. Ricardo defines rent as the difference in productive power between the best land and the marginal land in use (an extensive margin), and emphasizes that rent should not be confused with the amount paid to the landlord, which might contain remuneration for capital improvements (an intensive margin).

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation - On Rent - Chapter II

Rent is that portion of the produce of the earth, which is paid to the landlord for the use of the original and indestructible powers of the soil. It is often, however, confounded with the interest and profit of capital, and, in popular language, the term is applied to whatever is annually paid by a farmer to his landlord. If, of two adjoining farms of the same extent, and of the same natural fertility, one had all the conveniences of farming buildings, and, besides, were properly drained and manured, and advantageously divided by hedges, fences and walls, while the other had none of these advantages, more remuneration would naturally be paid for the use of one, than for the use of the other; yet in both cases this remuneration would be called rent. But it is evident, that a portion only of the money annually to be paid for the improved farm, would be given for the original and indestructible powers of the soil; the other portion would be paid for the use of the capital which had been employed in ameliorating the quality of the land, and in erecting such buildings as were necessary to secure and preserve the produce.[...] It is only, then, because land is not unlimited in quantity and uniform in quality, and because in the progress of population, land of an inferior quality, or less advantageously situated, is called into cultivation, that rent is ever paid for the use of it. When in the progress of society, land of the second degree of fertility is taken into cultivation, rent immediately commences on that of the first quality, and the amount of that rent will depend on the difference in the quality of these two portions of land. When land of the third quality is taken into cultivation, rent immediately commences on the second, and it is regulated as before, by the difference in their productive powers. At the same time, the rent of the first quality will rise, for that must always be above the rent of the second, by the difference between the produce which they yield with a given quantity of capital and labour....

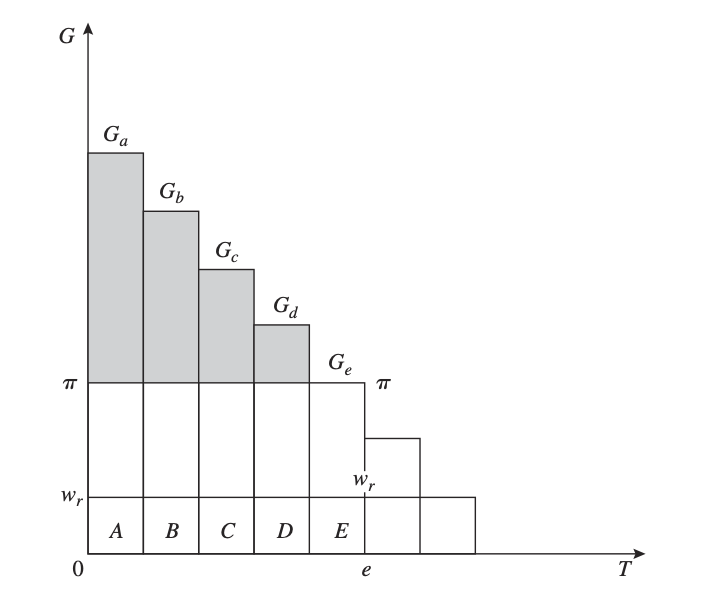

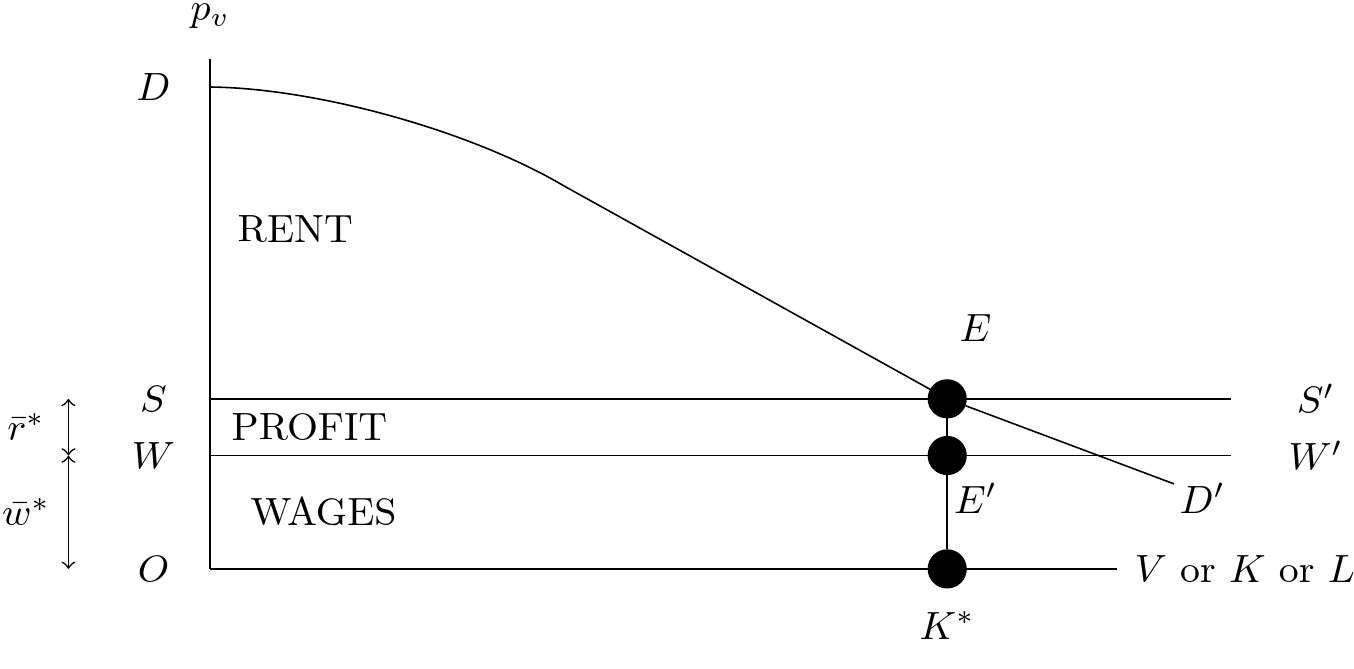

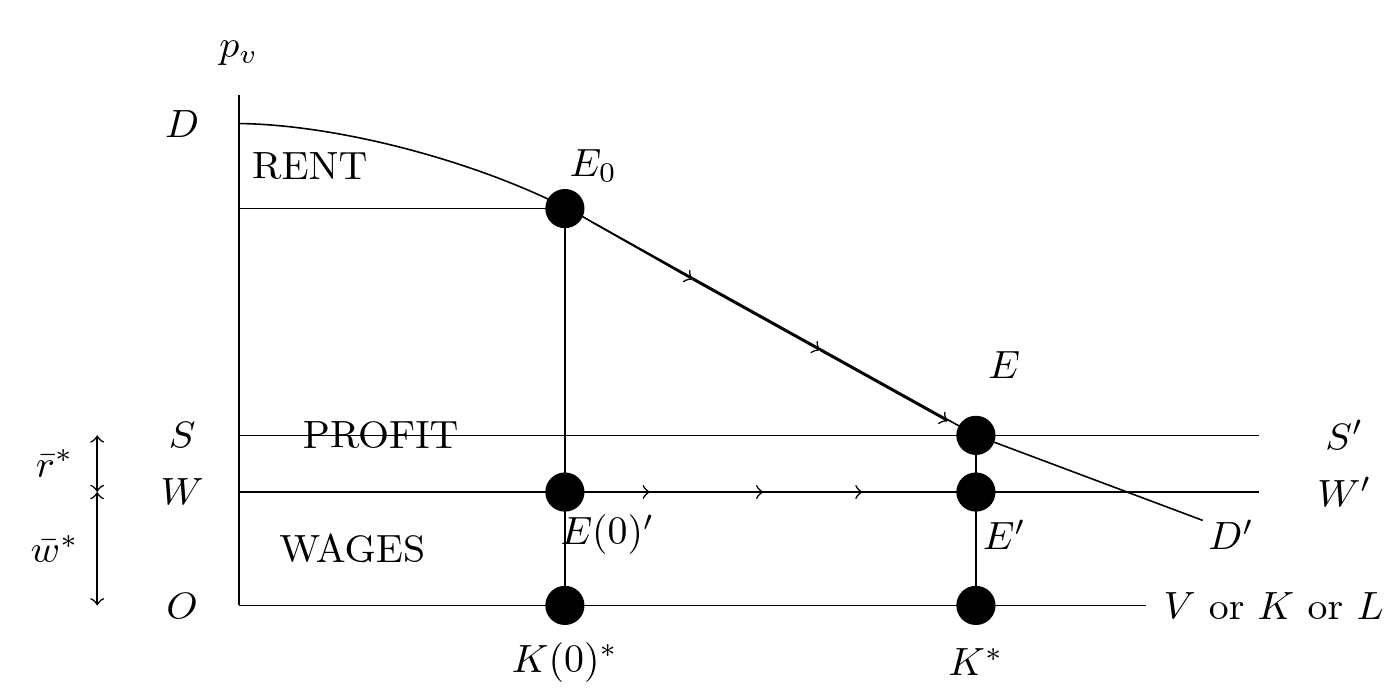

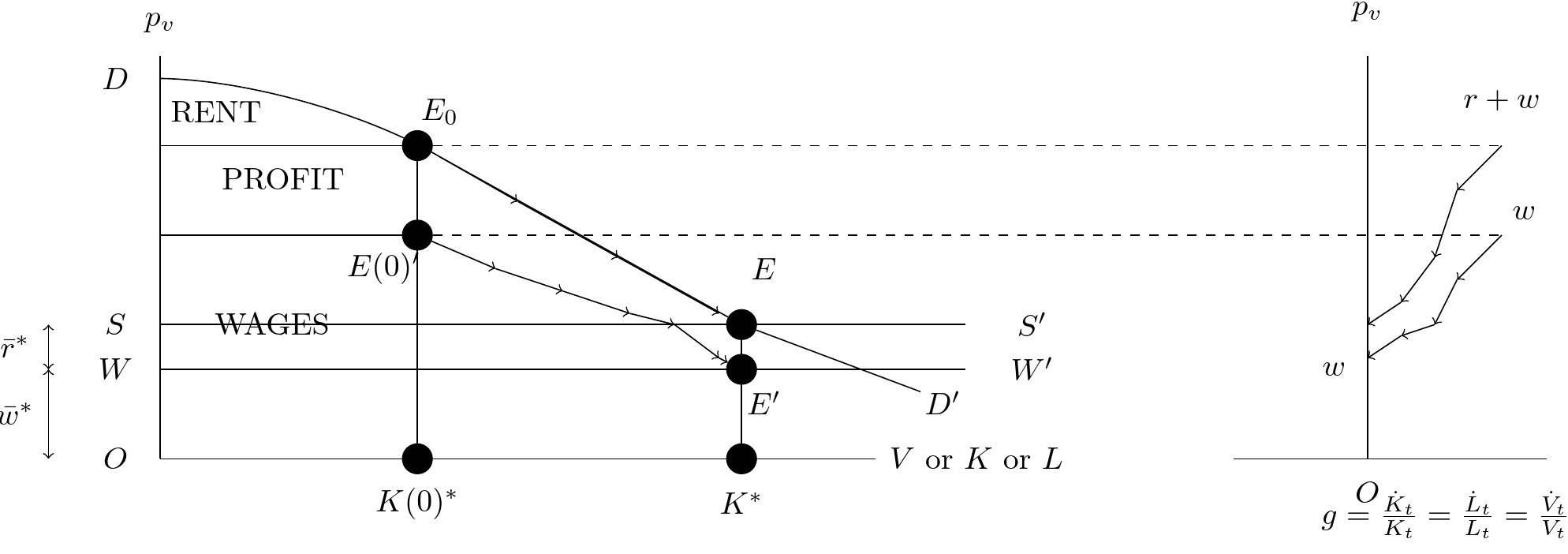

The following figure, which we will also use in the model at the end of this section on the Classics, shows how to determine the rent according to Ricardo. The horizontal axis shows the extensive usage of land T, with decreasing productivity going East, and the vertical axis shows the amount of grain G (net of seeds) produced. We divide the cultivated land into five types: A, B, C, D, and E, scaled in decreasing order of fertility. \(w_r\) is the long-run wage rate determined by the iron law[^fnric1]. Ricardo's assumption is that on the last piece of cultivated land, there is no rent. So land E produces a value of \(G_e\) and therefore, the profits are \(\pi = G_e -w_r\). Now, the second best land produces \(G_d>G_e\) and the difference between the value of these two productions is the rent paid to D. Because of competition, all the capitalists will earn the same profit rate since the product that can be obtained from intramarginal lands over and above that of the marginal land will be entirely paid up in rent.

Ricardo then adds a theory of growth: population increases, more land is cultivated which leads to a decrease in the profit rate and an increase in the rent. In the limit, Ricardo argued, a "stationary state" would be reached where capitalists will be making near-zero profits and no further accumulation would occur, but he saw this stationary state as far away in the future.

Ricardo then adds a theory of growth: population increases, more land is cultivated which leads to a decrease in the profit rate and an increase in the rent. In the limit, Ricardo argued, a "stationary state" would be reached where capitalists will be making near-zero profits and no further accumulation would occur, but he saw this stationary state as far away in the future.

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation - On Rent - Chapter II

The rise of rent is always the effect of the increasing wealth of the country, and of the difficulty of providing food for its augmented population. It is a symptom, but it is never a cause of wealth; for wealth often increases most rapidly while rent is either stationary, or even falling. Rent increases most rapidly, as the disposable land decreases in its productive powers. Wealth increases most rapidly in those countries where the disposable land is most fertile, where importation is least restricted, and where through agricultural improvements, productions can be multiplied without any increase in the proportional quantity of labour, and where consequently the progress of rent is slow.

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation - On Wages - Chapter V

...if we should attain the stationary state, from which I trust we are yet far distant...

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation - On Profits - Chapter VI

The natural tendency of profits then is to fall; for, in the progress of society and wealth, the additional quantity of food required is obtained by the sacrifice of more and more labour.

Ricardo suggested two things that might hold this law of diminishing returns at bay and keep accumulation going, at least for a while: technical progress and foreign trade. On foreign trade, Ricardo set forth his famous theory of comparative advantage. Using his famous example of two nations (Portugal and England) and two commodities (wine and cloth), Ricardo argued that trade would be beneficial even if Portugal held an absolute cost advantage over England in both commodities. Ricardo's argument was that there are gains from trade if each nation specializes completely in the production of the good in which it has a "comparative" cost advantage in producing and then trades with the other nation for the other good. Notice that the differences in initial position mean that the labor theory of value is not assumed to hold across countries -- as it should be, Ricardo argued, because factors, particularly labor, are not generally mobile across borders[^fn13]. As far as growth is concerned, foreign trade may promote further accumulation and growth if wage goods (not luxuries) are imported at a lower price than they cost domestically -- thereby leading to a lowering of the real wage and a rise in profits.

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation - On Foreign Trade - Chapter VII

Under a system of perfectly free commerce, each country naturally devotes its capital and labour to such employments as are most beneficial to each. This pursuit of individual advantage is admirably connected with the universal good of the whole. By stimulating industry, by rewarding ingenuity, and by using most efficaciously the peculiar powers bestowed by nature, it distributes labour most effectively and most economically: while, by increasing the general mass of productions, it diffuses general benefit, and binds together by one common tie of interest and intercourse, the universal society of 157 nations throughout the civilized world. It is this principle which determines that wine shall be made in France and Portugal, that corn shall be grown in America and Poland, and that hardware and other goods shall be manufactured in England.

Let us analyze the comparative advantage argument put forward by Ricardo. The critical point to be understood is that it is not the absolute advantage that matters but the relative productivity that determines the location of production. here is the numerical example that he presents in the quote below. The number in the table represents the number of man/hour needed to produce one unit of a good. Notice that Portugal has an absolute advantage: he is more productive in both industries. The assumptions are that labor is mobile only domestically and that goods are free to move internationally.

| England | Portugal | |

|---|---|---|

| Wine | 120 | 80 |

| Cloth | 100 | 90 |

A few elementary computations tell us: